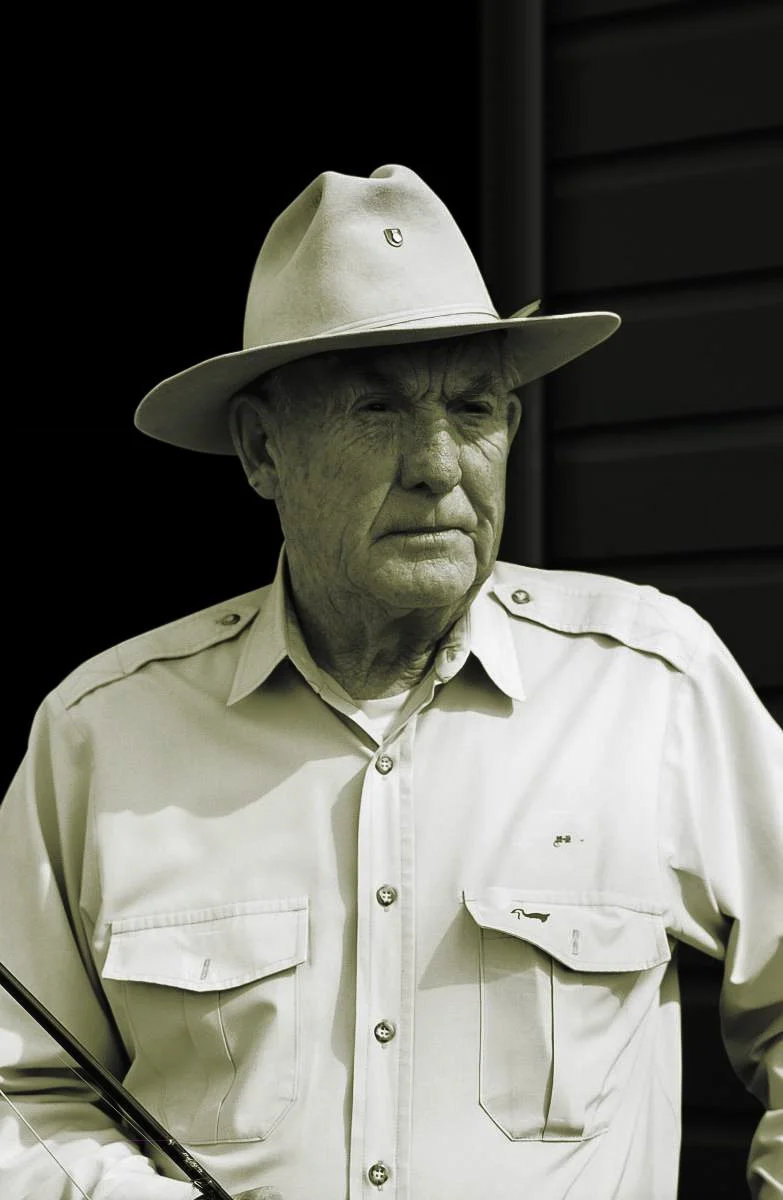

Bud Lilly

Walen "Bud" Francis Lilly was a man whose life embodied the very soul of fly fishing in the American West. He was more than an angler, more than a businessman, and more than a conservationist. He was a teacher, an innovator, a mentor, and a tireless advocate for the rivers, the fish, and the people who love them. He was, as the eminent angler Arnold Gingrich said, “a trout’s best friend.”

Bud was born on a kitchen table in the back of a Manhattan, Montana, barbershop in 1925. He grew up fishing and hunting in the Gallatin Valley, even delivering his daily catch to townsfolk as the Great Depression roared. Though he had many passions, his first love was baseball. By 15, his skills earned him a spot on a local men’s league team, where the scrawny redhead famously slapped a hit to left-center off none other than the legendary Satchel Paige.

An offer from the Cincinnati Reds promised a baseball career, but his service to the nation took precedence. As a Lieutenant J.G. in the Pacific Theater during WWII, he was wounded and awarded a Purple Heart after a Japanese Zero strafing run struck the USS General R.M. Blatchford near war’s end.

After the war, Bud married Patricia Bennett of Three Forks and became a high school science teacher, spending summers building his fly-fishing business in West Yellowstone. In 1961, he opened Bud Lilly's Trout Shop, which quickly became a cornerstone of Western fly fishing culture—a sanctuary where stories were traded like currency, and visitors, whether novices or experts, left enriched. His children, Greg, Mike, and Annette, all joined the business, guiding trips and establishing their own reputations as anglers. After Pat fell ill in 1981, Bud sold the shop the following year. Yet, his legacy endured: the shop continued to operate under his name for 35 years, a testament to the trust and reputation he had built. Decades after the sale, Bud's name remained synonymous with fly fishing, his influence living on in the stories, practices, and culture he had shaped—proof that his imprint went far beyond the riverbanks.

Lilly’s commitment to ethical fishing changed the landscape of the sport. He was one of the earliest and most passionate advocates of catch-and-release fishing, a practice now considered standard among western anglers. In his shop, he even started a club that awarded silver buttons as trophies to replace released trout—a small gesture that, as co-author Paul Schullery noted, “kind of replaced the trout as the 'trophy.’” This ethic wasn’t rooted in abstract environmentalism; it came from his deep respect for the fish and their habitats. By championing these practices, Bud helped make fly fishing more sustainable, more inclusive, and more meaningful.

Throughout his life, Bud served as a guide, not just on rivers, but in life. On the Madison, Yellowstone, and Gallatin Rivers, he led clients on days remembered not for the trout landed but for the lessons, experiences, and stewardship they carried forward. His famous quip when clients wanted to start fishing at 6 a.m., “Well, fine, I’ll put the coffee on tonight, and I’ll be over about 8:00,” was more than wit. It was wisdom born of decades spent studying the behavior of trout and the nature of the West. He urges visiting anglers to relax and enjoy the experience: “You’re out here to have fun. You wouldn’t fish 16 hours a day back home, and you don’t have to do it here.” These are more than tips; they are invitations to a fuller way of living.

Even after Pat’s passing, Bud’s dedication to fly-fishing and conservation never wavered. He channeled his energy into his work with Trout Unlimited and the Federation of Fly-Fishers, where his passion led him to meet Esther Neufeld, then the executive director of the Fly Fishing Federation. They fell in love, married, and raised two more children, Alisa and Chris. Bud’s advocacy continued through the books and film projects he created, all of which championed the preservation of the greater Yellowstone ecosystem.

As a founding member of Trout Unlimited, Bud served as an early bridge between anglers and conservation policy. His work with the Warriors and Quiet Waters Foundation helped returning veterans find healing and peace through fly fishing. He didn’t just fish trout streams; he protected them, advocated for them, and made them more accessible to others. Bud believed deeply in the role of public lands, and he was unafraid to speak up when access to or the health of those lands was threatened.

His written works, especially A Trout’s Best Friend and Bud Lilly’s Guide to Fly Fishing the New West, both co-authored with Paul Schullery, are considered foundational texts. The books are not just a manual—but a philosophy. In it, Bud shares his techniques—his preference for large streamers, his insights on hopper fishing, and his love of fishing during mountain rainstorms—but also his heart. It is infused with humor, grace, and wisdom.

The book’s resonance extended widely. Publisher Frank Amato called it “an indispensable introduction for the newcomer and a source of surprising new ideas even for the old hand,” while Gary Tanner, Director of the American Museum of Fly Fishing, praised its conservation ethic and sense of history. The legendary Lefty Kreh called it “a must-read book for anyone who enjoys the great trout waters of the western U.S.,” and NBC anchorman Tom Brokaw, an avid fly fisherman, referred to Bud as “a founding father of modern western trout fishing—and his book is an invaluable guide.” These endorsements reflect what anglers and conservationists alike recognized in Bud—an enduring voice of integrity, stewardship, and joy.

Though his books and plaques offer a glimpse into his impact, Bud Lilly's true legacy thrives in the mindful cast of today's anglers, in their understanding that the pursuit is rooted in care for the health of the water, the well-being of the trout, and the respect among fellow anglers. He was instrumental in shaping the sport into what it is now: a tool for environmental stewardship, a vehicle for timeless stories, and a source of solace and healing.

Bud's influence is deeply woven into the culture of Montana and American angling. He brought national and international attention to its waters not through marketing or flash, but through integrity and excellence. His life was a bridge: from science to sport, from wilderness to community, from solitary experience to collective responsibility.

Bud’s legacy endures at Montana State University, where he received an honorary doctorate and gave it the nickname “Trout U.” He played a pivotal role in creating the University Library’s Bud Lilly Trout and Salmonid Initiative, building what would become the world’s largest research collection for all things trout and salmonids. Today, the collection is maintained and expanded by his son, Chris Lilly, President of the MSU Library Board of Directors. Bud’s influence is also reflected in honors such as the Aldo Starker Leopold Wild Trout Medal and an induction into the Montana Outdoor Hall of Fame. Though not the first to champion catch-and-release, his role in making it mainstream transformed the sport. As Lefty Kreh noted, “He brought a new respect and understanding to trout fishing that few others could match,” a fitting testament to the enduring mark he left on the sport.

He was a devoted family man, and he welcomed everyone into his extended family of anglers. Whether through mentoring young guides, engaging in public discourse about conservation, or sharing a story with passersby while holding court with Esther in his latter years in front of their historic Three Forks home, the “Anglers Retreat,” Bud gave himself completely. Many are better off for his labor, his love, and the lasting gifts he gave us.

In his later years, Bud’s eyesight was diminished by macular degeneration, and he could no longer cast a line himself. Still, he rarely strayed from the riverbank, fishing vicariously through others—pointing out where to cast, which fly to use, and, with a wry smile, what they might be doing wrong.

Bud often said, ‘The trout can’t tell the difference between a $3,000 rod and a $30 one.’ He believed that fly fishing was never about the gear but about connecting people to the outdoors and sharing the complete experience—the essence of wild trout in wild rivers.

The “total experience.”

To say he deserves a place in the Catskills Fly Fishing Hall of Fame is true. But more than that—it feels right. Like putting a trophy rainbow back in the stream or going home skunked, but thankful for the sublime day on the water with your thoughts at peace, listening to the wind and the riffle.

He passed away in 2017 at the age of 91. His heart—big as a river, and just as generous—finally gave out. But his story, his impact, and his values are still with us. They ripple through every thoughtful cast, every trout released, every kid handed their first fly rod with a little advice and a lot of patience. He didn’t just change fly fishing; he elevated it.